It has been 25 days since that ominous conversation with the human resources department in his company but Nithin Shetty is yet to tell his family about what transpired. The son of a farmer and homemaker near Mysuru, Shetty had come to Bengaluru in 2013 with the same dream in his eyes as thousands of others before him: to find a job in the city’s storied software industry. But finding a job was easier said than done, particularly when you were from a new government college with poor facilities. “After coming here, I had to struggle for six months, doing courses and applying in different companies. I finally got a job in a software product startup after someone referred me there,” says Shetty. But though startups were the flavour of the season then, the company was unable to pay him a regular salary. He finally found the job he wanted with an MNC IT firm in one of the city’s biggest tech parks, in July 2016. Only to be told in less than a year that he should resign.

“Earlier, people who were given a bad rating would be put on a performance improvement programme. Now we have been told to take four months’ salary and leave in two days or serve two months’ notice and leave. I have appreciation letters from clients and testers but was given the last rating because I joined recently,” says Shetty, who sends money to support his family budget. Like him, his family believed his path would be smooth after he joined an IT firm. “If I tell them now, they will worry,” says the 25-year-old, who has been giving interviews at other firms but without success, so far.

Across town, near Electronic City, one of the country’s oldest and largest software technology parks, Thomas Jacob is in a similar quandary. After working in smaller firms in Chennai, Jacob moved to Bengaluru in 2002 to join one of the biggest software companies in India. Now, after 15 years in the same company, his supervisor is advising him to find another job. “We are hearing that by the end of June, those who have not yet resigned might be terminated,” says Jacob, who has been told that if he stays back he would not get any increments in the future.

Tech-tonic Shift?

Bengaluru might be flaunting its new tag of the country’s startup capital but, even now, it is the older software industry that is the bulk job creator, attracting people from different corners of the country. According to state government data, Karnataka is host to some 3,500 IT companies of which 750 are MNCs. The boom, which began in the ’80s with home-grown Infosys and US-headquartered Texas Instruments setting-up shop in the city, gathered momentum with large-scale hiring of coders to combat the Y2K scare in the West. Software parks with gleaming buildings and state-of-the-art infrastructure came up, fostering the notion that the city was on a par with other tech capitals in the world. With the lure of short and long-term postings in the US, swanky offices and the prospect of attractive salary packages being held out, moving to Bengaluru as a software engineer or “techie” became the favourite dream of the Indian middle-class.

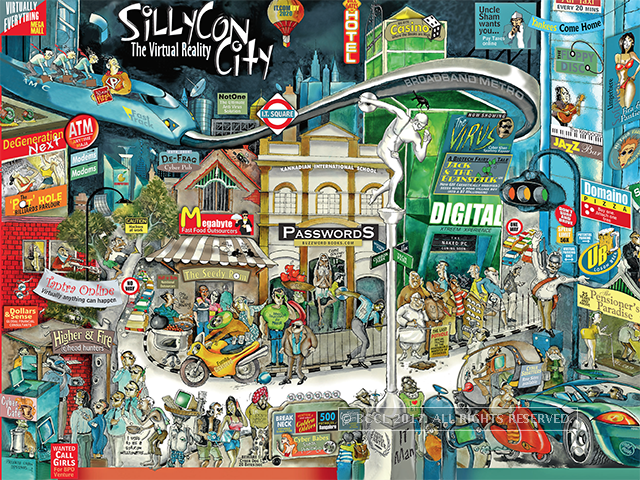

However, the city struggled to keep pace with this rapid influx of migrants that created sharp spikes in population growth, compounded by poor planning by successive governments, which led to the straining of every resource, from water to land. As former editor TJS George writes in Askew: A Short Biography of Bangalore, “the problem was that IT transformed Bengaluru in ways earlier bouts of industrialisation and immigration had not.” Other phases in the city’s development, such as the setting up of public sector industries, had come with planned residential enclaves for employees’ families and was also on a much smaller scale. Bengaluru-resident and artist Paul Fernandes, who has made a series of sketches on the city before the IT boom, says wryly that the “old Bangalorean” was caught unawares and did not quite know what to make of this transformation. “People did work hard before but it was generally a laid back city. There was none of the frenzy that you see today.”

But none of that was a cause for concern for people coming to Bengaluru in search of that IT job. The government has even estimated that the city would be host to 2 million IT professionals with the sector generating indirect employment for another 6 million (the city’s current population is close to 10 million). Given the recent cycle of bad news emanating from the infotech companies, though, this now seems like an optimistic prediction.

Tough Times Ahead

First off the block was Cognizant, which has over 2,60,000 employees, of which 1,50,000 are in India. There were reports that between 6,000 and 10,000 employees were being let go off even as president Rajeev Mehta wrote to employees last week, in an attempt to assure them that there were no layoffs and that the company is “committed to being a meritocracy.” Alka Dhingra, who tracks the IT sector at employment solutions company TeamLease, is expecting layoffs to touch 1,00,000 in the next couple of months, with Bengaluru bearing the brunt. “Being the IT hub with many jobs in software services, Bengaluru will be the most affected in the current round of layoffs,” says Dhingra.

Multiple factors are attributed to the latest retrenchment cycle: from the prospect of a stricter visa regime in the US and pressure to hire locally following Donald Trump taking over as president to the automation of certain jobs in the sector.

Rohan Kumar, for one, isn’t buying the theory that it is automation or Trump that led to his HR department calling him on April 10, to tell him to put in his papers. “The number of visas being issued is the same. And automation is a bigger threat for manufacturing and BPO sectors, not for core developers,” says Kumar, 28, who is convinced that the motive behind his company’s large-scale layoffs is to cut costs. “They want to get rid of mid-level executives and then hire fresh graduates who can do the same job for less. The irony is that, after being told to resign, I am still getting mails from job portals that my company is hiring for the same job profile,” he says. “The easiest way for the company to improve its margins is through layoffs. Bengaluru’s software companies are now like Maharashtra’s textile mills,” says a despondent Kumar, who was threatened by his HR team that they would snatch away his identity card if he did not resign. He plans to look for another job in Bengaluru for at least three months, before relocating to another city.

HR advisor Hema Ravichandar, who has over two decades of experience and specialised in IT, says all large IT companies have performance improvement plans and move the bottom 5 to 10% performers out of the organisation. “As the numbers have grown, the percentage under performance scrutiny also increases.

The ‘poor performance’ lens gets sharper, naturally, when business conditions get tougher,” says Ravichandar, adding that this happened in 2001-02, in 2008-09 and again, now. TeamLease’s Dhingra expects the IT hiring downturn to continue at least for the next couple of years. “Earlier, companies would hire engineering graduates and keep them on bench (without a project).

Now they will only hire when the need arises.” The larger impact of the IT downturn, or what economists refer to as the multiplier effect, is yet to be seen. Though he warns that this might be an extreme view, Narender Pani, professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, says one needs to keep in mind that there may also be a bigger reverse migration from the West, following incidents of racism and terror attacks. Additionally, any crisis management strategy would be hampered by the lack of data. “Currently, we don’t know how big the crisis is.

There are no macroeconomic estimates.” Will the IT industry have to abandon the city from which it has reaped so many benefits, he asks. “We need to know how many jobs are being created by IT companies here, as opposed to other locations.” If this kind of data is not captured continuously, the government runs the risk of being caught unawares, he warns. “Bengaluru’s garment export industry, for instance, lost out to Bangladesh of all places.”

But Bengaluru might not be as badly affected as is being suggested, says GK Karanth of the Institute of Social and Economic Change, terming it a “Trumped up” paranoia. “Trump himself seems to be more of a paper tiger. There might be talk of hiring locals but Indians have created a track record for themselves. And if Indian companies do hire abroad, they will finally become MNCs in the true sense.”

For now, many in the IT sector are still holding fast to the Bengaluru dream. Like 25-year-old Jatin Singh, a graduate from a premier engineering college who is now looking for another job after a bad rating in the current appraisal cycle. “This is still the Silicon Valley of India — no other city has the same opportunities in IT. I am sure the city will absorb me in two months,” says a confident Singh.

6 mins read

Bengaluru: Layoffs, job loss fears leave techies reeling under uncertainty