Walking through the Asaf Ali road, till the New Delhi Stock Exchange building, the cacophony is unmissable. Running up a flight of stairs in the building adjacent to the New Delhi Stock Exchange one reaches a large hall owned by Stirring Minds, which is home to a 3D printing workshop on a hot Saturday morning. Abhinav Singhal, Pranav Prakash, Shirsendu ‘Troy’ Karmakar and Shantanu Raghav, the founders of 3D Printing start-up Solidry are cheerfully working on setting up the workshop paraphernalia, getting the 3D prints organised and assembling a 3D printer. A gaggle of enthusiasts curiously peer over with noisy whispers as Karmakar continues to work on assembling the printer mopping his forehead occasionally. A few noisy minutes later after things are in place the workshop begins. From explaining 3D printing, to demonstrating how an object is created to answering questions to predicting its use in the real world, the workshop provides an in depth introduction to the concept. And it ends with the promise of meeting again to instruct people on how to build do-it-yourself 3D printers within the house.

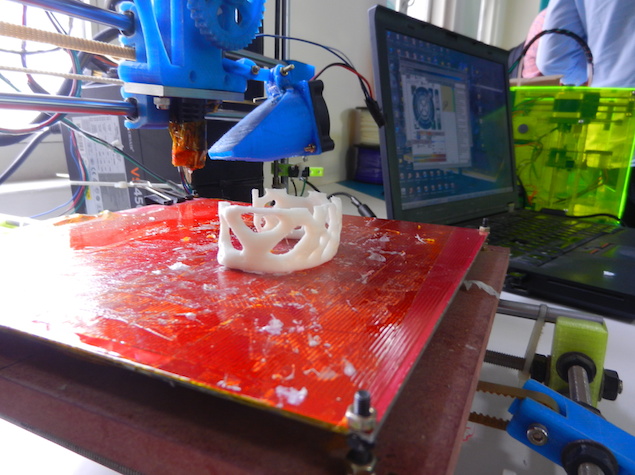

Solidry, which was started by the 20-something engineers with full time jobs at places like LinkedIn andSlideShare, is just the tip of a very fascinating iceberg. At the workshop, they created (and showed the rest of us how to create) objects that range from a ‘batarang’, to pen stands, and from card holders, to plastic jewellery all using biodegradable plastic.

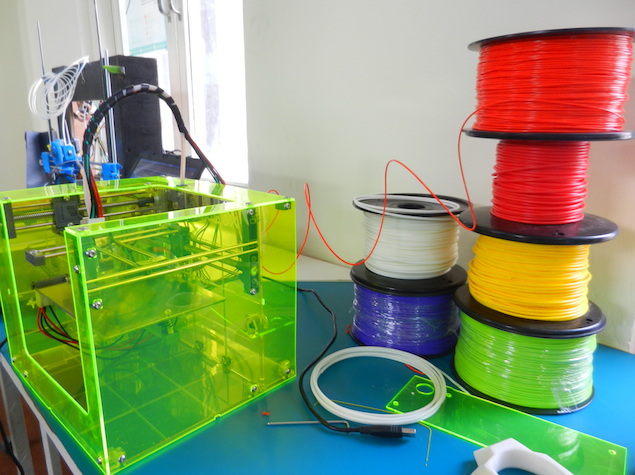

There are definitely problems for mass adoption, such as the time taken for a simple print. Solidry is a startup and they work with limited tools and resources, and printing a bracelet that was 15mm high and 5mm thick took around one and a half hours. The same was true in the case of our ‘batarang’. Also the finishing is something that has to be meticulous too. The technology is steadily improving though; “we are currently working with plastics like ABS, Polycarbonate PVA, rubber like materials called TPU, Ninja Flex amongst others. Once we are able to build a printer that can utilise multi-materials, it opens up a wide new range of possibilities,” says Prakash.

Explaining their enthusiasm about the process Karmakar says, “We got hooked onto the concept when we first heard about it during our engineering days. We wanted to purchase a 3D printer, but it was not cost effective. As a result we decided to build it all ourselves. That was the inception of Solidry, in June, 2013. We are focussing not only on popularising 3D printing but also in creating customised products for people and retailing them.” Karmakar and his team currently work with various plastics and metals. They offer users the freedom to upload their own designs, and create, hand finish and deliver it to them across India. In addition, they are also trying to enter into the manufacturing space wherein they could both create products on order and also retail their own designs.

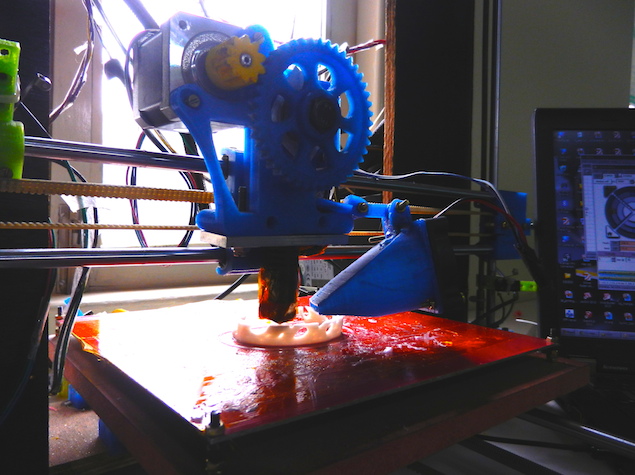

Extruding a print

3D printing involves extruding plastic filaments, slowly playing them in layers to build 3D objects. At the Solidry workshop, while Singhal works away at explaining the real world uses of 3D printing in the field of medicine, the home made printer works away religiously at extruding hot white plastic in a concentric pattern on a flatbed. At one end of the extruder is the hopper for feeding the white plastic line, which has a diameter of 1.75 mm. Like other normal printers it too is connected to a laptop nearby where the design parameters have been keyed in using software called Slic3r. The extruder works along three axes – X,Y,Z – to create the final finished product. The Slic3r tool enables users to convert their digital designs, and wireframes into a model that can be accepted by the printer for printing. Once the material is fed into the hopper it is continuously drawn into the heater where it melts at 155 degree celsius following which the extruder nozzle points it at the base and the plastic is added in successive layers according to the design imprinted.

Raghav, who is the youngest member of the group, explains that it works against the current industry manufacturing processes of subtractive manufacturing. “When we use CNC based manufacturing the focus is usually on cutting the design out from the stock material. That involves a lot of wastage. Additive manufacturing basically is adding the material on a set design, which leads to virtually zero wastage.”

Singhal, who is currently working in developing 3D prints in the field of bio-medicine also says that the designs can help replicate bone structures, create organ implants, and others. “It becomes important to consider this during times of surgery. For instance if a body part has to be created or an implant fitted it takes time to create the same. There might be inaccuracies and also it involves a second surgery to insert it which increases complications. A lot of these issues can be solved using parts created from 3D printing,” he says.

There are interesting possibilities for the future. In India 3D printing is still at a domestic hobbyist use which has limited its reach as of now. But there are a wide range of possibilities. Singhal points out that with its unique challenges India provides a vast landscape for research and innovation in this field. “It should get better from here on,” he says with a smile.

The road ahead

The Dutch firm, Dus Architects, are in the process of creating what would possibly be the world’s first 3D printed house. Using materials that are completely recyclable (all one needs to do is reheat it to use it), it involves significantly reduced transports cost and also reduction in pollution. In a report by the Guardian, the 3D house could be a very scaleable model on which modern day cities of the future can be built.