Let’s face it: Intel’s track record of anticipating trends in computing is, in a word, lousy.

Let’s face it: Intel’s track record of anticipating trends in computing is, in a word, lousy.

Intel didn’t truly embrace low-power computing until Transmeta forced its hand. The company has repeatedly squandered opportunities in the phone by fumbling its Strong ARM processor, and Intel’s internal graphics program has struggled to keep its head above water until recently.

Recent trends imply nothing has changed: One could argue that former chief executive Paul Otellini was shown the door because of an inability to, once again, capitalize on mobile — specifically, the tsunami of tablets toting ARM silicon inside.

But, as analyst Jon Peddie noted, Intel does one thing right: It sees mistakes, and it fixes them, dragging its customer industries along with them. In May, Intel shifted its corporate motto to “Look Inside,” implying that Intel technology might be found unexpectedly in products beyond the PC. Now, Intel is busy driving the PC forward, but also hedging its bets with any number of non-traditional devices. The common thread? Those devices must compute, communicate, and consume less power than before.

So what does that imply? Seven trends that are changing the computing industry: the lessons of this week’s Intel’s Developer Forum.

1. Desktops are dinosaurs

It’s a bit premature to declare the desktop dead. But the roaring minitowers of years past have been pushed upward into the rarefied air of the gaming PC. Instead, the desktop has evolved into one of two things: a docking station for a notebook, or an ultra-small-form-factor “desktop” device that’s actually portable.

Scattered throughout Intel’s technology showcase were what Intel rather awkwardly calls NUC’s, or New Units of Computing. Just 4 inches by 4 inches by 1.5 inches high, the latest version of these tiny boxes can actually house Intel’s latest “Haswell” processor — which in turn has enough graphics horsepower inside its “Iris” graphics accelerator to run some pretty sophisticated modern games. While it seems silly to consider anything but a notebook for a low-cost PC these days, the NUC certainly looks like a strong candidate for the last gasp of the mainstream desktop.

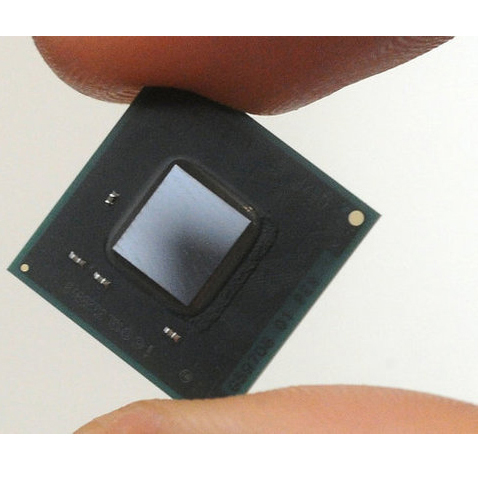

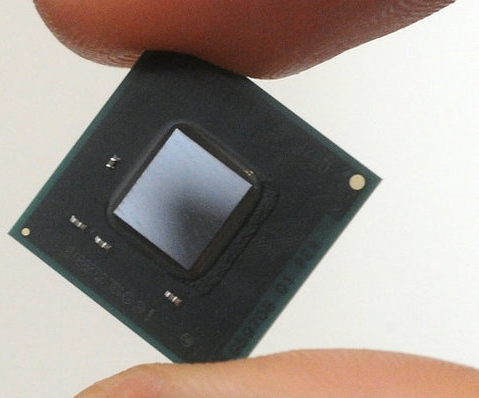

Intel’s 14-nm “Broadwell” Core chip, due at the end of the year (and in PCs in 2014) should enable truly fanless designs, Intel executives said. That has implications for the NUC, as well as the…

2. Two-in-ones: the new Ultrabook

In years past, Intel and Microsoft both pitched new ideas and new directions for the industry to adopt. Several, to their credit, were merely ahead of the curve, such as the SPOT watch and the original Tablet PC. One of the ideas that truly failed was 2008’s Mobile Internet Device (MID), an ugly combination of a small touchscreen, Linux, and an SSD.

But Intel’s ideas to combine touchscreens and portability helped pave the way for the Ultrabook, the 2011 Intel concept that has evolved into the “Harris Beach” design that now straddles dozens of Ultrabook designs using Intel’s latest “Haswell” Core processor.

Now, Intel has taken that a step further with a new category of “hybrid,” “convertible,” or “two-in-one” devices, all describing the same product: a detachable tablet that can be docked to a keyboard for stability and extra battery life. Two-in-ones will use Intel’s “Bay Trail” Atom chip, which offers both dramatically improved battery life as well as increased performance, eliminating the sluggishness that characterized the previous “Clover Trail” notebooks. In the tablet configuration, these new designs offer the thinness that we’ve come to associate with tablets, as opposed to the relative chunkiness of Microsoft’s Surface.

The bottom line: So far, this looks like the next step in the evolution of the mainstream Windows notebook.

3. But Atom isn’t low-power enough

And the Core begat Atom, which begat Quark…simply put, Intel realized that even optimized for low power, the Core could only go so far to address the emerging market for all-day computing. Thus, Intel designed the Atom — which arguably went a bit too far in establishing a low-power foothold, with not enough performance.

Now Intel has reached the same crossroads: the Atom is simply too big and bulky for the Internet of Things, and a new architecture was needed: Quark. Chatter among the press and analyst corps says the Quark architecture is some sort of cut-down Silvermont chip, the technology underlying Bay Trail, the Merrifield chip for phones, and the Rangeley networking processor.

Quark is one-fifth the size of the Atom and will operate at one-tenth the power. Those numbers are vague enough that we can’t intuit much. But the power goals and the fact they’re synthesizable says that they’re an attack on ARM, whose embedded chips seem to have an inside track on the Internet of Things. Intel’s facing an uphill battle, of the likes it fought with AMD: using the brute force of its advanced manufacturing capabilities as a broadaxe to wield against the nimble rapiers of the ARM licensee legions.

4. Natural-user interfaces are a blessing in disguise

Turns out that the real world is a complicated place, filled with unknown objects and unfamiliar people, all interacting in complex and seemingly unpredictable ways. That poses an enormous and lucrative problem for any number of companies, from interpreting speech and gestures, to finding directions, to altering recommendations based on the proximity of friends. As the hardware interface between the virtual and real world, Intel is well positioned to suck in petabytes of data that can be analyzed by third-party software and services — all running on Intel hardware, of course. And what it can’t do with its own CPUs and graphics chips can be done with new lines of optimized silicon that Intel is specifically creating.

5. Can you hear me now? Guess not

IDC (a division of the International Data Group, which owns PCWorld) said Wednesday that smartphone sales were expected to top 1.01 billion devices in 2013, over 65 percent of the “connected device” market that includes desktop PCs, notebooks, tablets, phones, and other devices. By 2017, smartphones will make up 70.5 percent of the space. And yet Intel had nothing to say about the phone, except to reiterate its design win inside the Lenovo K900 and its efforts in the LTE space.

Yes, Intel could be prepping for a dedicated “Merrifield” launch for the phone market in the near future, but it needs to get on the ball. Intel still isn’t a player in the phone market, and it looks like this won’t change soon.

6. Wintel is a convenient fiction

Microsoft and Intel have shared power within the personal computer for the better part of a generation; historically, Intel would introduce a new, more powerful computer, and Microsoft’s software would bring it to its knees. That’s changed. Only games require a high-end CPU and discrete graphics card, and that means that Microsoft has turned to the tablet and even phones for its OS and productivity software.

With Bay Trail, Intel chips can now power Android and Windows alike. And Intel continues to support the Google-powered Chromebook with its fourth-generation “Haswell” desktop chips. Intel’s hearty embrace of Google has been met with Microsoft’s adoption of ARM in phones and notebooks, like ex-lovers trying to one-up the other.

7. Moore’s Law is Intel’s ultra combo

Quite frankly, there is little Intel feels it cannot solve by manufacturing muscle alone. Each year, like clockwork, Intel ushers in either a new processor revision or a new manufacturing node. And the tick-tock model continues apace: “Broadwell,” the name of Intel’s 14-nm shift, will launch before the end of the year, chief executive Brian Krzanich said at IDF. That means Intel’s traditional PC chips in the notebook, desktop, and server space will see their operating power cut, to the tune of 30 percent or more. That’s an easy way to keep the PC train rolling.

The PC industry — Intel included — has had its existential moment. Intel committed to a new direction: mobile, mobile, mobile. IDF simply told the world what Intel’s competitors figured out several years ago.